Iran’s Key and Historical Role in Cultural Trade; Hamidreza Ghorbani

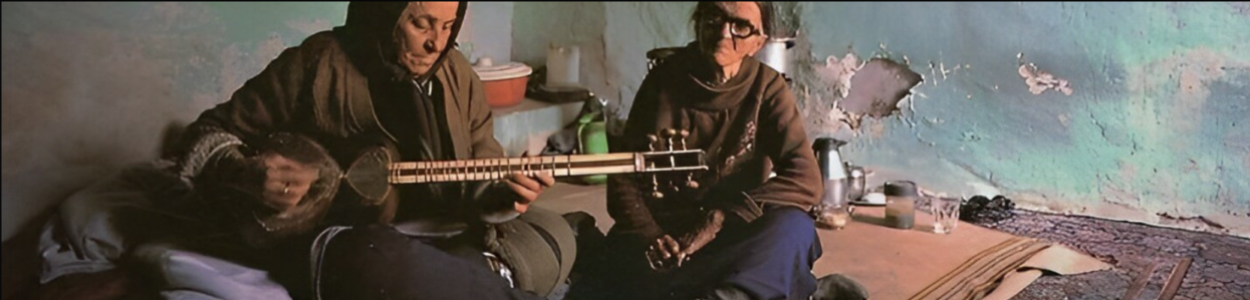

In ancient times, travel was the work of adventurers, merchants, explorers, and conquerors. These travelers spent years on the roads staying in different places and had to become familiar with the culture, traditions, art, literature, and way of life of the people they encountered. Usually, servants, guards, carriages, horses, livestock, food, and various goods accompanied them. They also had entertainers with them – musicians, poets, storytellers, comedians, and dancers. They were the true cultural envoys of their time.

The dialects, manners of speech, new musical instruments, handicrafts, and customs of these travelers influenced how people in different lands perceived their own cultures. Music was an important avenue through which cultures influenced each other.

As one of the key posts along the Silk Road, Iran played a significant role in cultural trade. There is ample evidence of musical instruments traveling from the Iranian plateau to China from the seventh century AD. The flow of music and poetry from Bukhara and Samarkand towards the east and west of the plateau shaped the music and poetry of this region.

With the advent of new modes of transportation and communication in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, cultural relations underwent major changes, relegating Iranian music to the margins of musical exchange compared to that region. Did a cultural Airbus fly over Iran in such a hurry as to overlook its rich heritage? What are the reasons behind this omission?

Exoticism in Music and the Global Tendency towards New Discoveries

In today’s world, where geographical borders are erased in a matter of minutes or hours instead of months or years, musical styles such as Chacha, Mambo, Salsa, Raga, Saga, Tropic Music, Qawwali, Afrobeat, Griot, Fado, or Konga are no strangers to the ear. Central African music has become acquainted with the sounds of the Aymara of South America, and Indian ragas with the tunes of Scandinavian polkas. The world has always had an eye for new discoveries in music. Cuban African elements, Bossa Nova rhythms, non-European instruments, including the Oud and the Pipe, and Sufi music have a clear presence in pop, rock, and R&B. New names like Desert Blues, Fusion, Bollywood Music, and Sufi Trance have become part of the musical lexicon.

So why, among the wide range of musical instruments that populate the so-called global music scene, do we not hear the name of the Tar? The Shur scale in Iranian music is the same. The rhythmic Chahar Mezrab is unknown to many. The modes of music that witnessed continuous expansion from the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries have been sidelined today. Meanwhile, Indian music, which shares numerous characteristics with its Iranian counterpart, enjoys tremendous popularity worldwide. Aesthetics aside, I would like to offer some reasons for the disparity between the two musical traditions.

Why Did the World Pay Attention to Indian Music?

Like other countries around the world subject to colonization, India adopted and incorporated many of the characteristics of the colonizing mainland. The influence of the English language can be considered the most obvious example. It facilitated important interactions between the colonizer and the colonized. Migration to and from the colonies and the slave trade further intertwined traditions. Nowhere can we see this cultural blending better than in music.

With the end of World War II, Europe and the United States entered a new phase of international challenges and crises. The division of Germany, France’s problems in Cambodia, the start of the Cold War and the nuclear confrontation, the emergence of a threat called Cuba as a symbol of communism a few kilometers south of the US border, the rise of a superpower like China, the Vietnam War, McCarthyism, women’s and civil rights movements in the United States, all trapped the Western world in turmoil from the 1950s onward. The risk of World War III was very high. The world was on the verge of collapse, and with it, a thirst for peace and tranquility intensified among the new generation.

Who spoke of peace? What could distract minds from the overwhelming crises that had reached the shores of the post-war world? The political philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi, with its Hindu and Buddhist undercurrents, Eastern mysticism, Sufism, incense, Krishna, sexual liberation, psychedelic drugs, etc., offered ways out. For Western youth, the East, its culture and traditions, its music, was an escape.

Many factors played a catalytic role in the popularity of Indian music: the Buddhist leanings of iconic figures like John Lennon and George Harrison, the use of the Sitar in “Norwegian Wood” from Rubber Soul. Ravi Shankar’s intersection with Yehudi Menuhin and the production of West Meets East. The mystical magnetism of Jim Morrison and The Doors. The popularity of psychedelic and hard rock and the taste of Eastern melodies in the music of Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, and other rock bands. Concerts such as Woodstock and Bangladesh; the friendship between Zakir Hussain and John McLaughlin and the musical theories of Peter Gabriel after his departure from Genesis, are only the most immediate.

If initially, minor influences of Indian music caressed the ears of European audiences, today its music is generally known and appreciated. Which in itself is considered exotic, audiences can easily sit for several hours and listen to its various tunes (in different modes). In other words, the transitional phase helped familiarize audiences who were unfamiliar with the Indian musical tradition. It even helped promote the music of neighboring regions such as Tamil Nadu (Sushila Raman) and Pakistan (the Qawwali music of Abida Parveen and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan).

The same can be said about Francophone or Latin American music as well.

So Why Did the World Neglect Iranian Music?

Since ancient times, Iran has been at the crossroads of trade and at the intersection of wars and confrontations. Two major conquests (Arab and Mongol) were influential in determining how the people of the Iranian plateau confronted the outside world. Although the country never became a “colony,” its people strategically learned how to serve invading armies without relinquishing their integrity. In modern history, the Russian Empire and the British Empire tried to divide the land between themselves. They met with some successes but never achieved complete political control.

These are some of the reasons why Iranians did not fully surrender to the invading culture, unlike the Indians. Instead, they raised their defenses. Even when France, Germany, and, more recently, the United States tried to gain control in seemingly less hostile ways, they met with resistance. This situation caused national traditions and customs to be driven underground. Iranian modernists accepted “coexistence” with foreign influences, or rather, the appearances of Western culture. Those who were loyal to their ethnic culture preferred to lock it away, while modern intellectuals blindly followed the Western model.

In major population centers, among the various immigrant neighborhoods formed around religious and ethnic affiliations, no identifiable Iranian enclaves exist. It is even sometimes difficult to distinguish an Iranian by their appearance, as Iranians seemingly melt into the pot around them. Meanwhile, Westerners residing in Iran benefit from the famous “Iranian hospitality.” Iranians, unlike Indians, pride themselves on playing the role of host rather than the conquered. Could it be that the combination of this social leniency and the habit of hiding traditions also structures Iranian music?

From the beginning of the twentieth century, Iranians who had the opportunity to study in Europe brought many of the offerings of Western culture back to the country. In music, an attempt was made to create a “scientific” framework for Iranian classical music based on European notes and instruments. However, little has come of these efforts. The same trend can be observed in pop and rock music as well.

Today, in contemporary Iranian music, we see strong streaks of non-Iranian influences. Furthermore, the pattern of mass migration, especially after the Islamic Revolution in 1979, has given rise to a generation of Iranians who, through migration to various countries around the world, have weak ties to their musical past. Iranian music in exile may use Persian words, but it rarely attempts to draw upon the rich reservoir of its existing musical repertoires.

In the past century, the Qajar’s preoccupation with appeasing modernity, the Pahlavi’s attempt to create a secular state towards the West, and the reciprocal Islamic reaction have created an identity crisis for Iranian music. Three main trends can be identified among Iranian musicians: those who want to preserve traditions at all costs and disregard external influences, those who completely surrender to Western models in the hope of salvation from traditions, and those who allow external influences to shape their music without losing traditions. The first two have been effective in keeping Iranian music hidden from the global scene. Only the third group is in favor of exchange and dialogue between cultures.

At the same time, the global mass media show less interest in what Iranian music has to offer than in musicians who belong to the third group, the Western media presents them as jewels in a ruin called Iranian music.

What Does the Future Hold for Us?

The world is looking for exotic developments. But these events have an expiration date and a short lifespan, world music is in desperate need of new material. Ears are desperate to hear new sounds and voices, desperate for new roots, different traditions, and new forms of knowledge. Many regions around the world, with their current social conditions, show potential to introduce their music and culture to the world. Iran, Afghanistan, Southeast Asia, the newly independent countries of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan are just a few of them.

This desire can be clearly seen among Iranian musicians, especially those who have been exposed to Western music throughout the ages, from the medieval to the classical and contemporary periods. For example, the French-Persian group Nur has tried to combine Spanish Cantiga and Gregorian chants with Kurdish and Persian repertoires. By performing their music live in Europe and Tehran since 2000, the group has been actively searching for what has been lost in the evolution of music in the East and West of the world. The introduction of musical notation and the systematization of classical music in the West led to the removal of certain aspects of music that were supported by oral traditions. On the other hand, Iranian music has largely preserved its oral and improvisational features. In this way, Nur tries to bring into Western music what it had abandoned since the Middle Ages – the art of improvisation. The collaboration between good musicians, four of whom are of French nationality, has so far resulted in the release of an album called Alba.

Examples of such intercultural music can also be found in the works of a rural group such as Jahle. Jahle is an earthenware pitcher used as a water container in some villages in Hormozgan province in the Persian Gulf. Alongside local instruments such as the Ney Jofti (double reed flute) and the Dohol (bass drum similar to the Indian Mridangam), Jahle gives a unique sound to this region to the music. At the same time, the group uses blues, rock, rap, and reggae rhythms and melodies to add variety to Bandar Abbas music, which itself is heavily influenced by Ethiopian and Zanzibari musical traditions.

With its ancient history, regional and ethnic diversity, diverse traditions and customs, and rich literature, Iranian music certainly deserves to be recognized, heard, and seen. Today, the world of music awaits a fresh event, and perhaps Iran will be the site of cultural transformation.